Research Insights, August 12, 2020

Investing in Solutions: The Case for Essential Housing

Cities across the United States have long grappled with how best to tackle increasing unaffordability for many of their residents, to varying degrees of success. The economic fallout from the coronavirus and the ensuing shutdowns have brought back into focus the critical importance of equitable policies for all sociodemographic groups in providing basic necessities, including quality housing.

While much of the existing research and commentary on the affordable housing space has been centered around the potential investment opportunities arising from coordination with state and local municipalities to leverage tax credits or subsidies to supply much-needed low-cost housing to the community, less has been dedicated to addressing and solving for what some have coined the “missing middle” – that is, those renters who can neither qualify for affordable or subsidized housing in the traditional sense, nor afford the luxury housing that has represented the majority of new projects that have been delivered during this business cycle.

Yet it is this gap, which includes many of those essential workers to whom the U.S. owes so much, that needs attention. With many investors increasingly focused on the positive impacts of their investments, we believe a strategy that targets creating and maintaining essential market-rate housing may offer a compelling opportunity to both serve the needs of communities and investor stakeholders.

Defining what we mean by Essential Housing

There is a myriad of labels used to describe any housing that is not “market rate”. These descriptors – affordable, attainable, low income, workforce, Section 8, rent protected, essential - are often used interchangeably, muddling the nuances of the sector. So, what do we mean when we talk about essential housing, and how does it differ from some of the more well-known housing types?

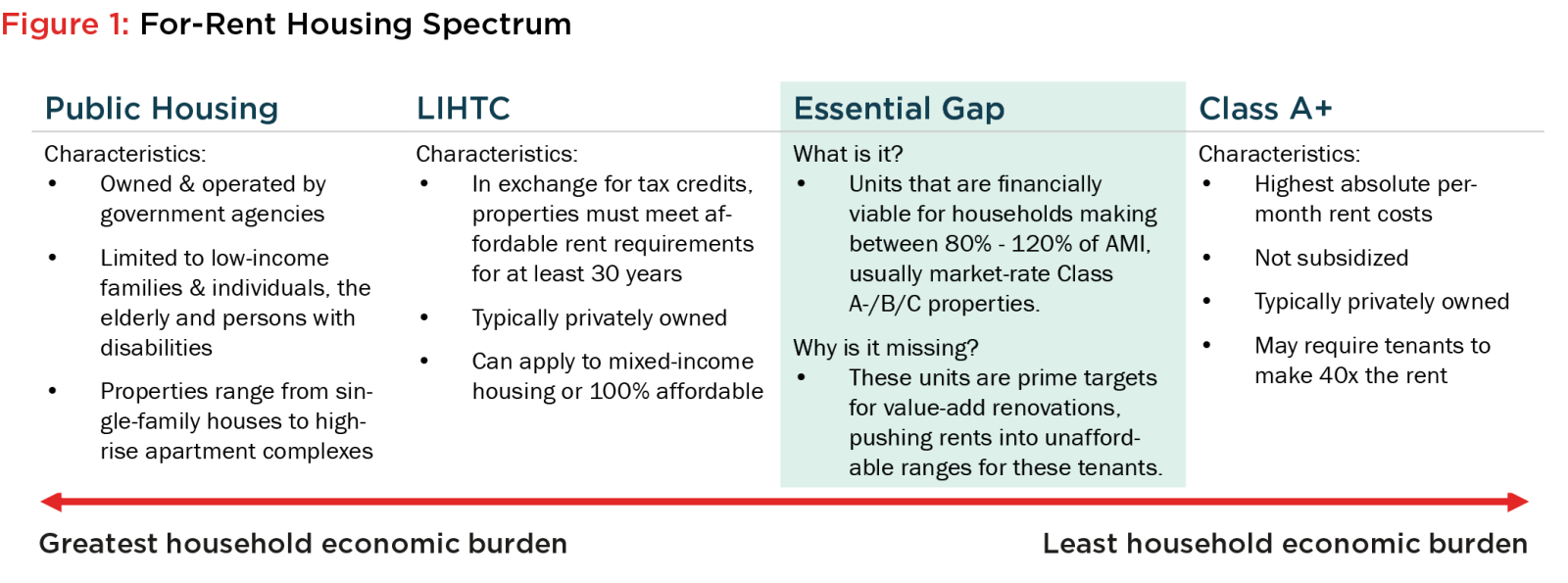

Perhaps the best way to contextualize the gamut of for-rent housing in the United States is to think of it as a spectrum, moving from those properties owned and operated by governmental housing authorities and fully subsidized on the left to the most expensive Class A+ market-rate apartments on the right (Figure 1). Units that cater to households making more than 80% of an area’s median income (AMI) who are above the cutoff for governmental subsidy but do not qualify for or cannot reasonably afford the new luxury product are what we’ve designated as the “essential gap”. It is this gap that has, and continues to be, woefully undersupplied, but also creates an opportunity for the socially minded investor.

Demand and (lack of) Supply

At first glance, imagining that a household making 80-120% of AMI would have difficulty finding housing is hard to fathom. But the reality is, in most cities across the country, making 120% of AMI does not ensure there is a quality apartment available at an attainable price point. To better illustrate what we mean, let’s take an example in what could be considered to be a reasonably affordable place to live, Miami, Florida.

According to the recently revised U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Income Limits for fiscal year 2020, the median income for Miami-Dade County was $59,100. This means that a household making 80% of AMI earns $47,280 and a household making 120% earns roughly $70,920 annually. Most of the guidelines and commentaries on housing affordability deem 30% of one’s income as an appropriate target for how much someone should pay for housing costs without being rent burdened – this means that at 80%, a household could afford to pay $14,184 per year in rent, or roughly $1,182 per month, or ~$1,800 at 120%.

A quick search on CoStar, which maintains a database of virtually every apartment community, for conventional multi-family properties with an average 1-bedroom effective rent of $1,182 or less yields a map full of results spread across the county (894 properties, to be exact). With approximately 160,000 households in Miami-Dade falling within these income brackets, one might think this cohort is adequately supplied by the available multi-family inventory.

But these aggregate figures mask other factors that underscore the necessity of a strategy focused on creating or maintaining this type of essential housing, namely:

- The number of units vacant at any given time in this price range: There have been, on average, less than 4% of these properties vacant in any given quarter over the last twenty years in Miami-Dade County.

- The distance to primary employment nodes, and the added cost of distance: Those units that are vacant and available for occupancy are strewn across the county. While many are within driving distance to major employment nodes, nearly 20% are in locationally disadvantaged areas. In fact, according to the Center for Neighborhood Technology, a more comprehensive view of affordability combines both the cost of housing and the cost of transportation (as transportation is typically a household’s second-largest expense), suggesting properties that are geographically further from employment nodes lack locational efficiency may actually be more expensive overall. And this says nothing as to the availability of other essential amenities such as grocery stores, childcare and the like.

- The propensity for rents to rise: The units we identified across the Miami-Dade county reflect the pool of accessible apartments to the household making 80% of AMI today and reflects a moment in time. A change in ownership strategy that results in a value-add renovation program with the objective of increasing rents could bring these rents to an unattainable level, thus reducing the amount of available options even further.

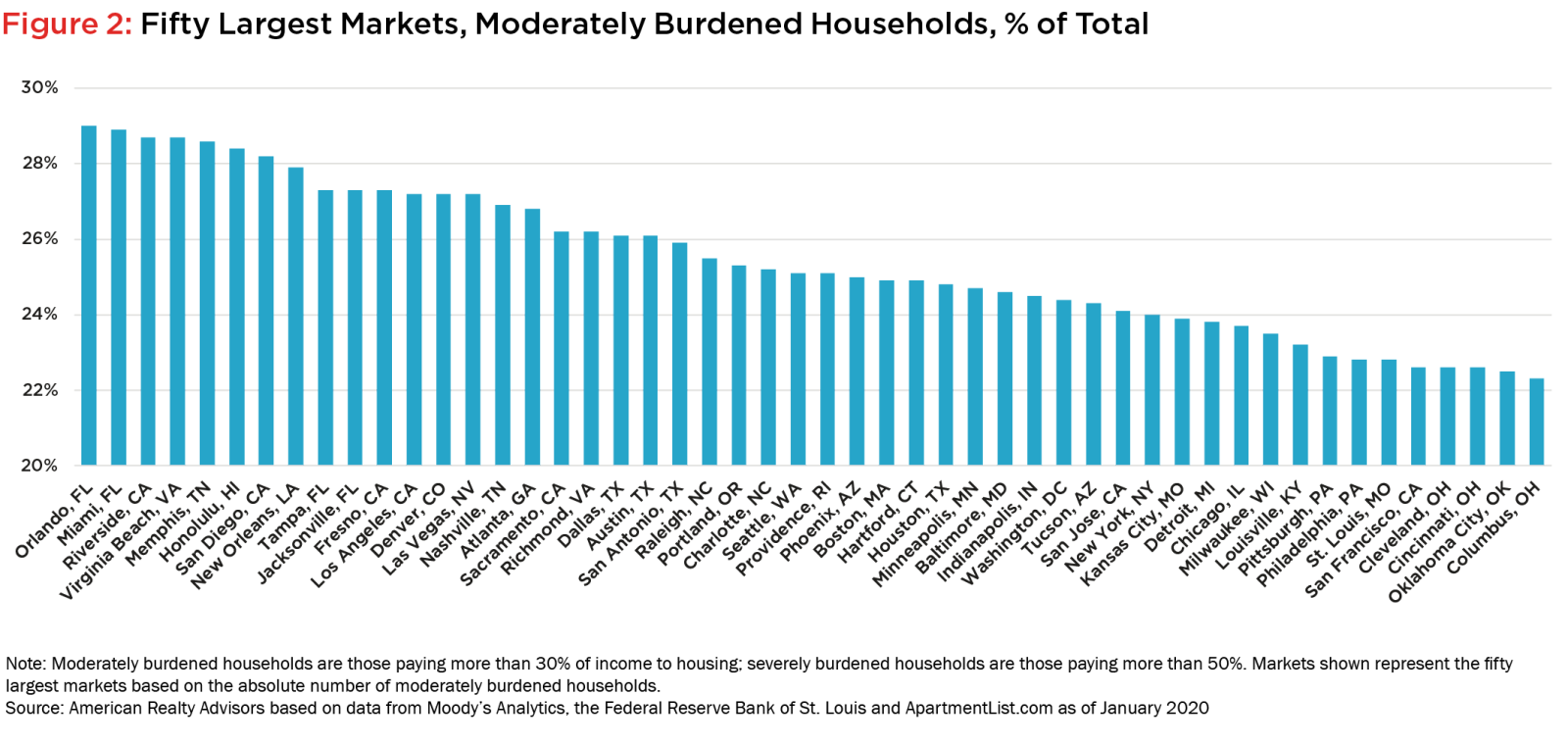

While this example may seem like it would be isolated to only the most expensive cities, the reality is that this is a national problem. The fifty metros with the largest number of moderately burdened households1 comprise a combined 6.2 million households, or roughly 25% of metro households on average. This list includes some of the higher cost “usual” suspects such as New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco, but also includes many metros with perceived affordable costs of living, such as Houston, Tampa, and Tucson (Figure 2).

We know that there are well in excess of six million households across the country that are moderately rent burdened (with an equally large number considered to be severely rent burdened2) who need more affordable and accessible housing relative to their incomes. The next logical question might then be “Why isn’t there enough housing that is within reach for these households?”

The demolition of outdated/obsolete units to make way for either new luxury multi-family construction or different uses entirely, value-add repositioning of older product to drive rents that are no longer attainable, and lack of new supply all contribute to the shortage of available housing for this cohort. According to CoStar, nearly 200,000 Class B/C apartments have been demolished across the United States in the last twenty years. At the same time, the ability for investors to earn a sufficient return on development of buildings with lower per-unit rents has been increasingly challenged given rising land and construction costs, discouraging much new supply and putting further pressure on this renter cohort.

Fundamentals and Performance

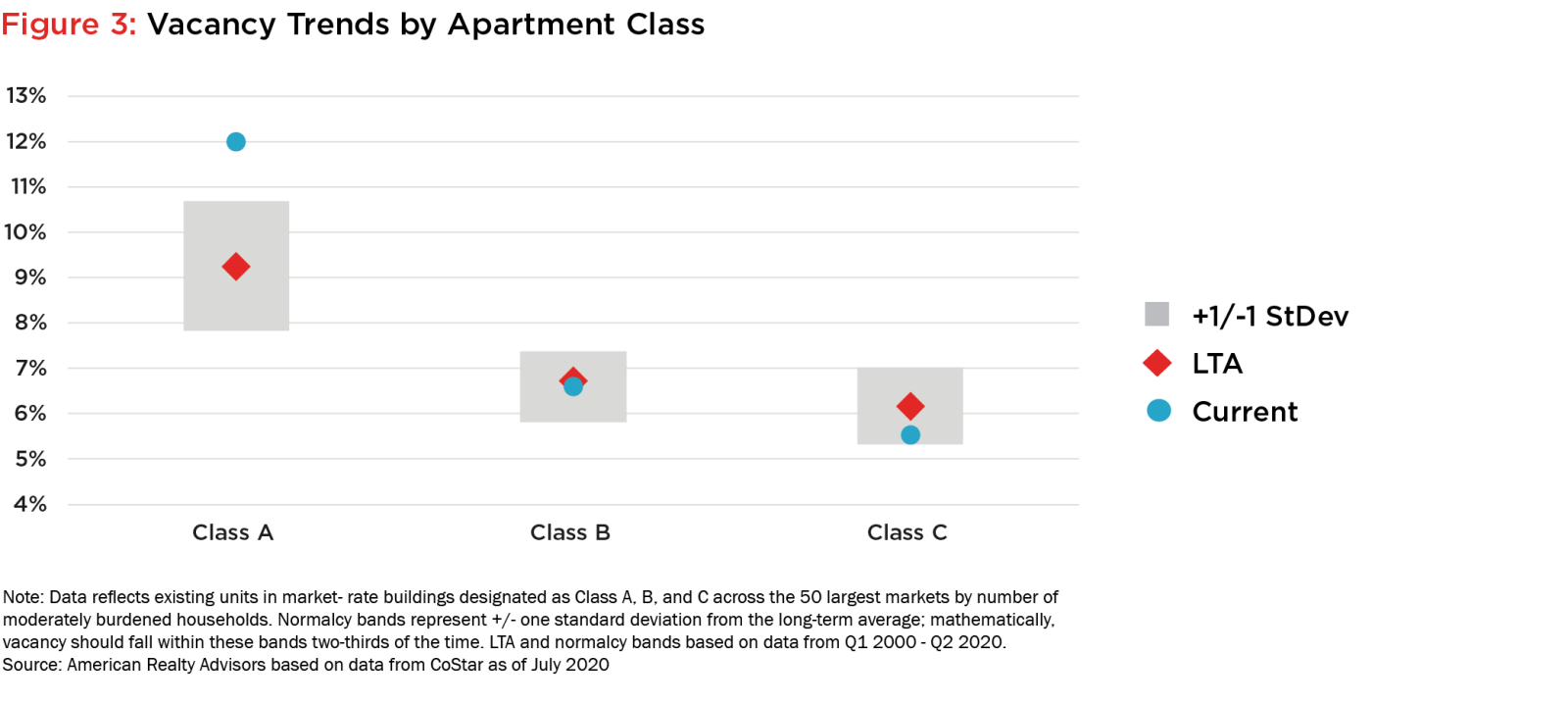

The opportunity in this imbalance is that fundamentals in this segment are compellingly strong for those investors who can navigate the complexities of acquiring or delivering it. Using data from across the fifty most burdened markets (as shown in Figure 2), we’ve looked at aggregate historical vacancy ranges between Class A, B, and C apartments.3 As Figure 3 clearly demonstrates, Class B units tend to have a low long-term average vacancy (or put another way, high average long-term occupancy) and that vacancy tends to fluctuate within a much more narrow band two-thirds of the time compared to both Class A and Class C buildings. Why is this the case?

As we alluded to earlier, deliveries tend to be in the Class A space by virtue of the quality and cost of construction, which has created wider swings in vacancy and elevated the long-term average amidst new supply. So, while Class A apartments achieve higher rental rates and have historically offered investors attractive returns, there is an inherently higher volatility of vacancy in any given period when compared against Class B units.

Some may rightly wonder “If Class B units are in such high demand and Class C rents intuitively are even lower, why have Class C buildings exhibited a modestly more volatile historical vacancy? Wouldn’t renters opt to rent even cheaper apartments?” While a bit of an oversimplification, we believe that Class B is in the most insulated position economically given the fluidity of its appeal to different renter cohorts. During times of strong economic growth, Class C renters may feel confident in their ability to pay a slightly higher rent for a higher-quality Class B product, while in times of economic hardship, some Class A renters may actually shift into Class B buildings to save money or offset any job losses.

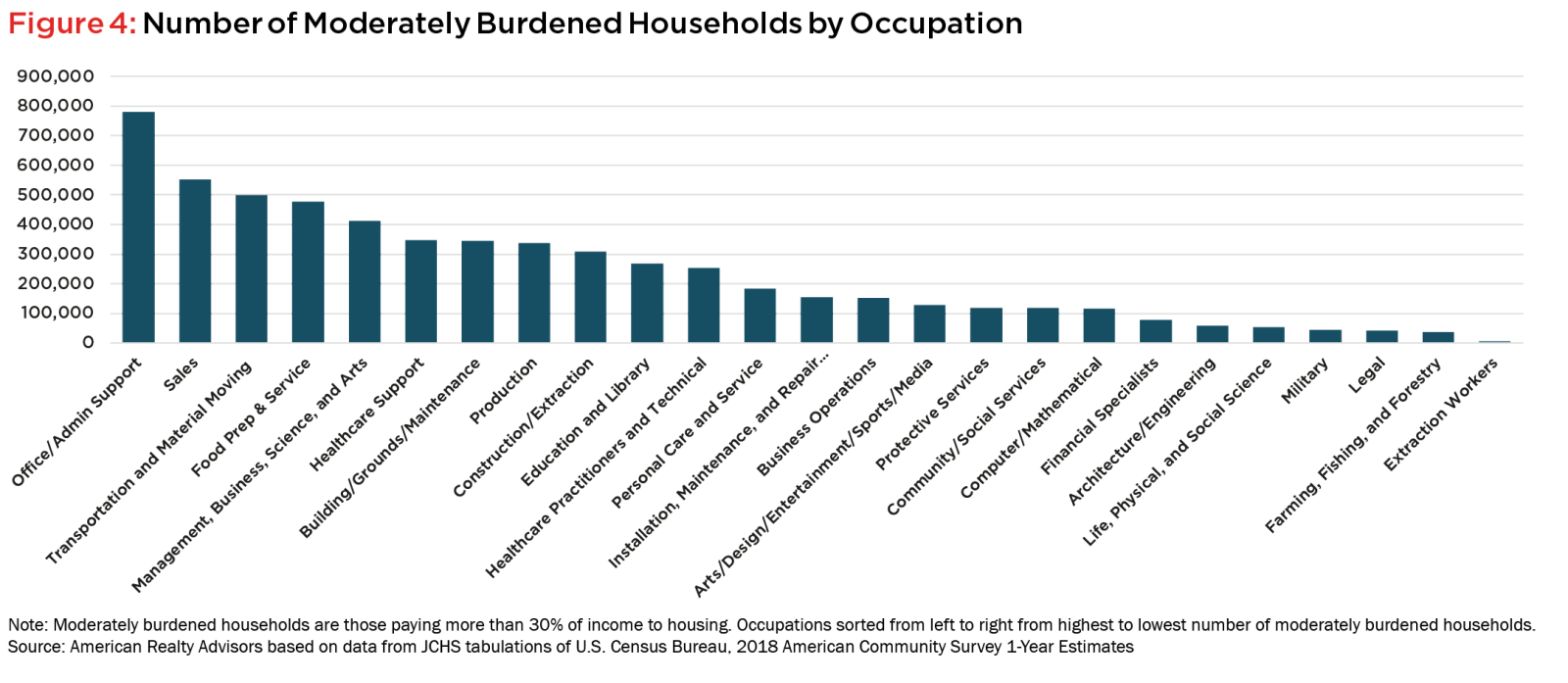

Given this, Class B tends to fare well in most economic environments because of the diverse composition of those renters who need it. Renter households that are moderately cost burdened in the country today are not isolated to lower-paid hourly jobs but are also found in many “white-collar” industries like healthcare, management, office and administrative support, and business operations (Figure 4).

This diversification is also particularly relevant in light of the swift and severe contraction in employment related to the coronavirus, where hourly workers seemed to be impacted the hardest. According to data from RealPage, Class A and Class B rent collections for the month of May were just 1% apart as of May 27th (at 93.5% and 92.5%, respectively) while Class C buildings struggled meaningfully more to collect rents due, with just 87.5% of rents having been paid by that date.

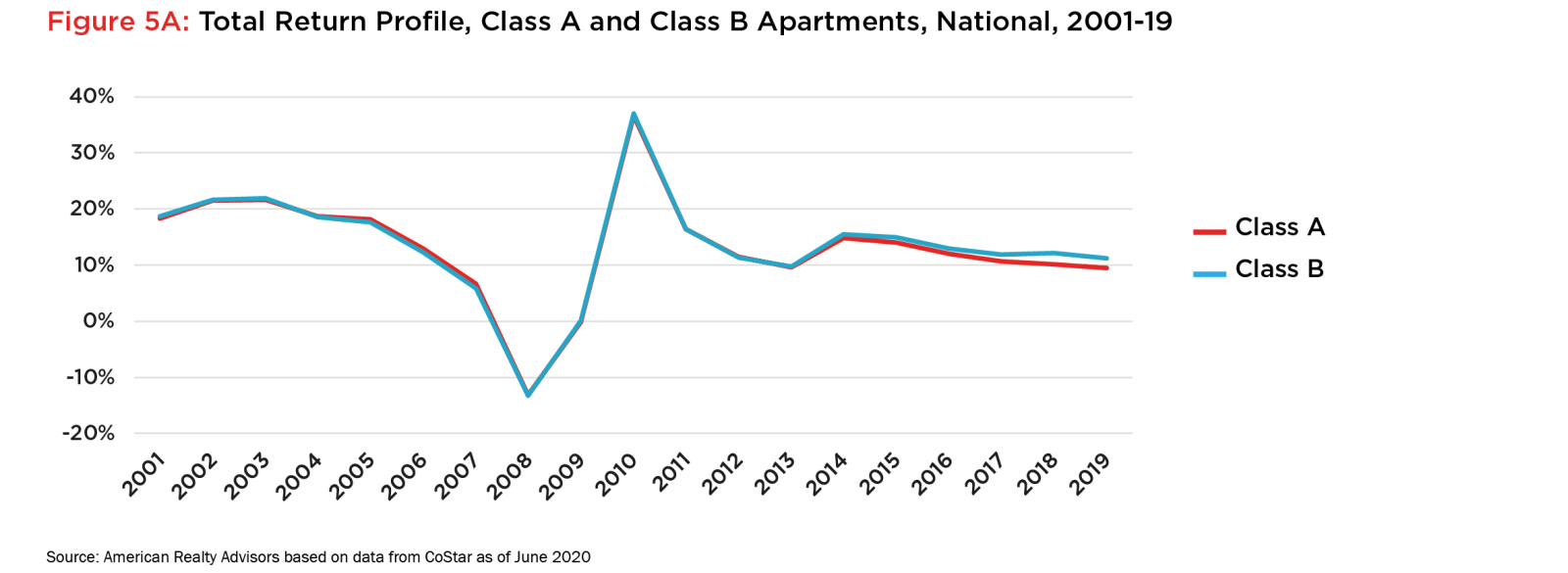

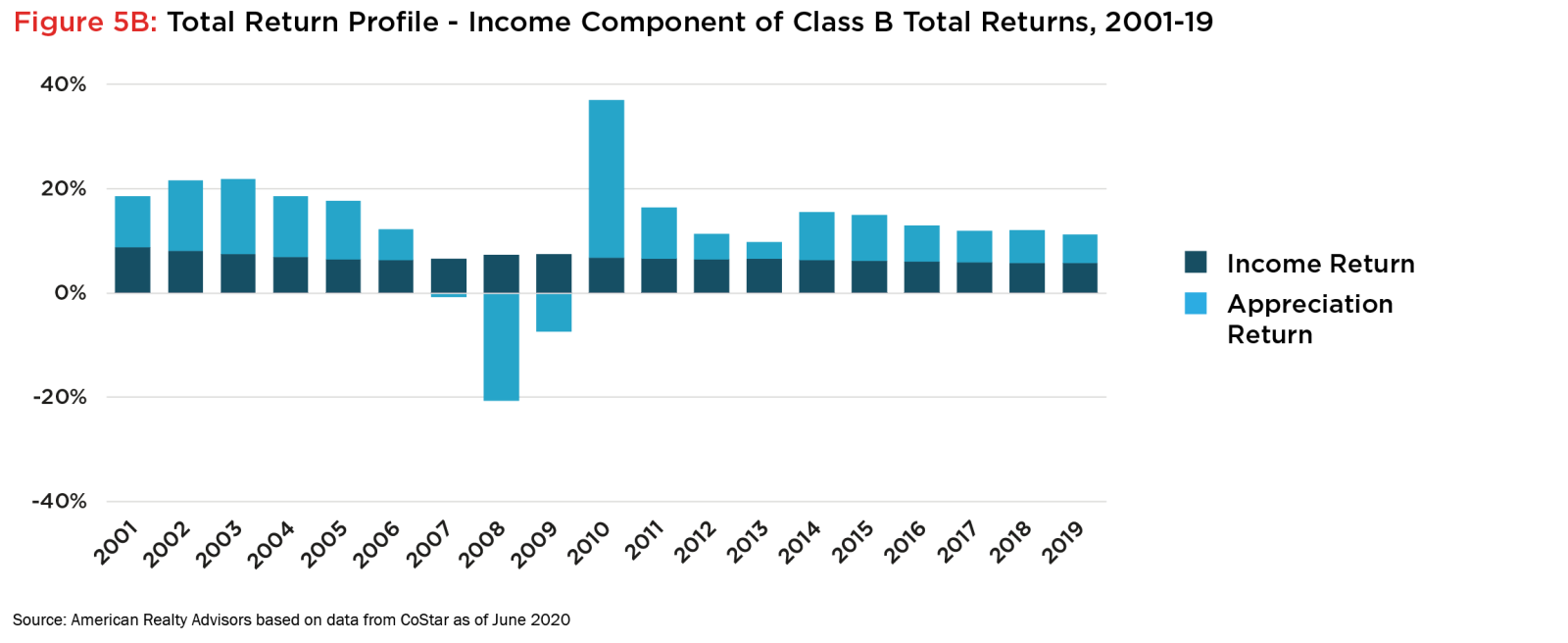

It is this combination of higher occupancy and resilient income that has led Class B apartment returns to outpace Class A buildings by 35 basis points over the last nineteen years, with much of the outperformance occurring over the last five years (Figure 5A). Class B returns are underpinned by a steady income component even during periods of economic duress, which can create a stabilizing element in investors’ real estate portfolios (Figure 5B).

Social Impact

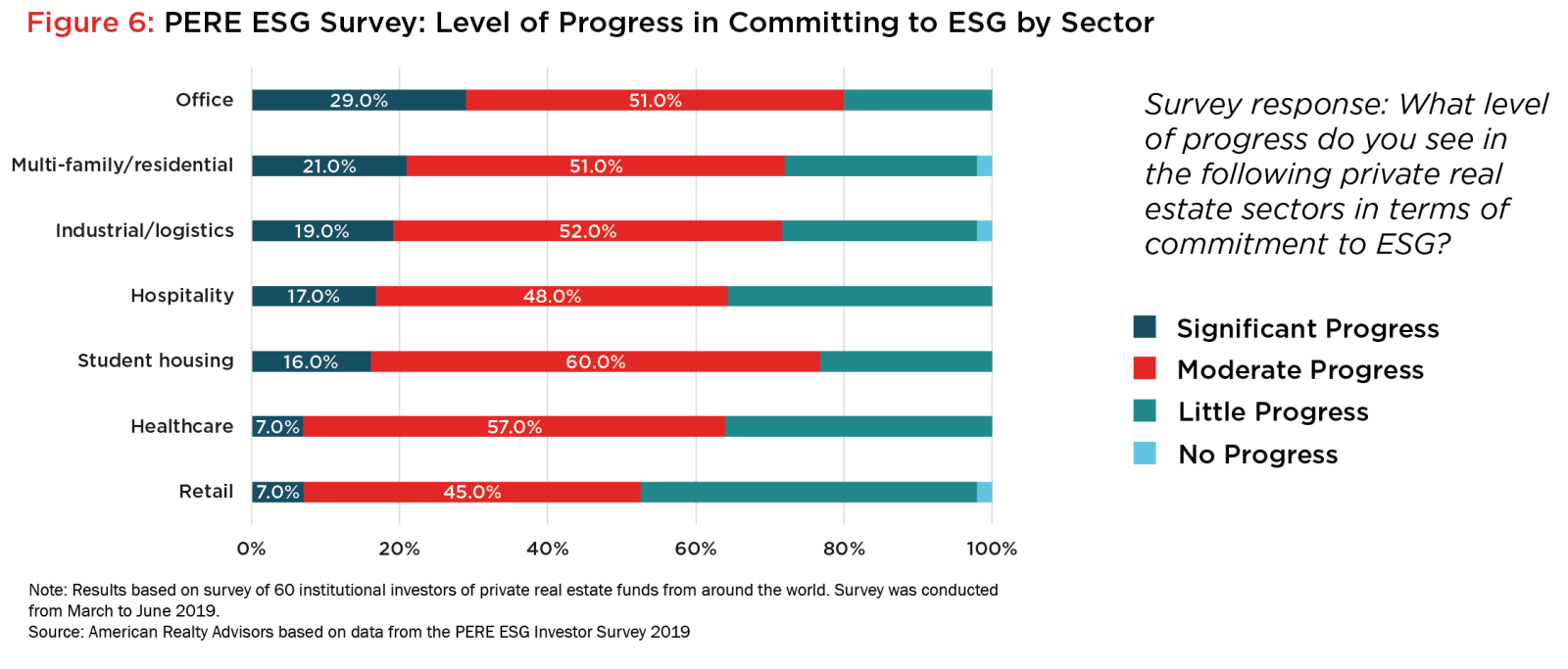

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations have been gaining greater prominence among institutional real estate investors’ requirements over the last decade. No longer secondary to financial metrics, investors have demonstrated their commitment to these pillars with their wallets – according to a recent PERE survey, nearly 70% of investors surveyed said ESG principles either play a major role or serve as a guide in investment decision-making, and 43% indicated they would not invest with a manager that did not have a defined ESG policy.4

Institutional managers have responded to the call, moving towards greater adoption of ESG initiatives to satisfy client requirements and do their part in fulfilling their obligations to the communities they invest in. Their actions have largely been centered on the “E”, as this is the category that is perhaps easiest to quantify and applies most directly to buildings’ bottom lines. The social aspect has been somewhat slower to evolve, but it too is coming increasingly into focus.

And the multi-family sector is in prime position to continue to lead the way when it comes to ESG adoption. According to the same PERE survey, investors perceived only office as having shown greater progress towards ESG than multi-family (Figure 6).

By its very nature, essential housing is an answer to community and investors’ needs, serving to maintain the number of attainable apartments available to renters while simultaneously satisfying the desire to “do well by doing good”.

Competitive Landscape

So – the appetite is there, as is the potential to really progress the multi-family sector’s social sustainability. Yet despite this compelling combination of investor interest, strong fundamentals and attractive returns, there are few investment vehicles in the marketplace today targeting this specific subset of the renter population with the intention of maintaining affordability. While affordable housing funds have been around for years, those that cater to the middle-income population of apartment renters remain largely nonexistent, as affordable housing funds have historically focused their efforts on low-income housing. This is because this segment has tended to offer the greatest government subsidies and tax credits, which have served to cushion these strategies’ anticipated returns to acceptable levels for investors absent the ability to raise rents. A handful of large banking institutions and development firms have committed capital towards affordable housing initiatives this cycle, though these have largely been focused on LIHTC properties.

While there are a handful of fund managers who have created offerings to serve the moderate-income segment, it has typically been part of strategies meant to capture renters across the income spectrum. These funds tend to include projects that leverage government subsidies for strictly low-income renters, assets with an equal mix of rent tiers for units priced for all income classes, and assets they market as luxury apartments.

It is these types of mixed strategies targeting the wider gamut of affordable housing needs that are beginning to emerge. The institutional money management world has only recently acknowledged the growing need for increased housing for “the missing middle”, though few firms have committed resources in pursuit of the attainable segment.

What this suggests to us is that the middle-income piece is being blended into a broader discussion of affordable housing without adequately addressing the nuances of this specific segment. A strategy that attempts to offer all things to all people may find itself faced with an operationally challenging portfolio of assets and/or sponsors that lack the expertise to implement them all to the same degree of execution simultaneously. We believe strategies that are solely focused on targeting and serving one segment through a higher level of specialization and expertise may prove to keep costs in check and offer more attractive returns. These types of strategies may also serve as a complimentary sleeve to those investors that have already forayed into affordable housing via LIHTC or like-kind funds.

Opportunity Set

While the lack of supply and return profile suggest a compelling investment opportunity, the competitive landscape demonstrates that few have ventured to explore this part of the market, instead opting to pursue LIHTC or mixed-income properties that leverage some form of governmental subsidy. In our view, this “missing middle” represents an untapped opportunity to tackle the social element of investors’ ESG goals while creating a steady, income-oriented return profile that isn’t tethered to municipalities’ coffers.

That being said, the very dynamic that makes the market-rate essential housing opportunity so compelling also makes it challenging to enter. Value-add players who can afford to pay more on the expectation of higher returns post-renovation creates competition, in turn putting downward pressure on essential housing returns in most primary markets. This may mean going beyond the most obvious markets or locations within primary markets to offset some of these pressures.

While there is virtually no metro in the country that isn’t faced with affordability concerns, we believe the best opportunities for long-term essential housing strategies are those that target markets with a sizable enough overall population to support the multi-family class fluidity dynamics and where median rent growth has outpaced median income growth over the last decade. This includes places like New York, Los Angeles, Boston and Seattle, but also select secondary or even tertiary cities such as San Antonio, Memphis, Indianapolis, Sacramento, Virginia Beach and New Orleans (Figure 7).

Conclusion

With individuals’ homes currently serving as their residence, their workplace and their social sphere, the coronavirus has re-emphasized the necessity of accessible housing for all. Yet to date, the availability of appropriately priced housing for middle-income renters has been woefully inadequate to satisfy the level of demand.

Part of the reason there has been limited inertia in solving for this segment is the challenges associated with acquiring it – simply put, it is harder to compete on pricing for marketed opportunities against buyers whose strategies envision higher rental rates after a renovation program.

Yet as we have seen, there has been an increasing appetite from investors for strategies that allow them to do well by doing good, and several forward-focused institutional managers (who have recognized the compelling demand case) have endeavored to answer the call. But there is considerable room to expand the institutional response.

For those investors to whom achieving a stable, income-oriented return while simultaneously satisfying their ESG agenda is appealing, an essential housing strategy may be best suited to achieve those goals. It requires adopting an approach with a long-term view dedicated to maintaining affordability of market-rate essential housing across the country.

1Moderately burdened households are households paying more than 30% of income to housing but less than 50% as defined by HUD.

2Severely burdened households are households paying in excess of 50% of income to housing as defined by HUD.

3While we are using market-rate Class B apartments as a proxy for essential housing fundamentals, the reality is existing properties that fit this strategy may span classes, depending on per-unit price point and market.

4Source: PERE ESG Investor Survey 2019